Discovering the ‘real’ Aloha has been no easy task.

Even with our dogged determination and collective ‘nose’ for uncovering the minutest detail, securing secondary and tertiary sources of information about Aloha and the entire Wanderwell Expedition was difficult.

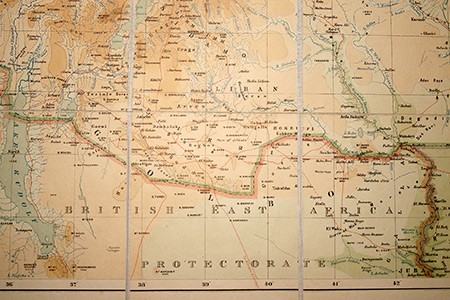

However, one day, Aloha’s daughter, Valri, placed a dust-covered tin box in our hands; no one had set eyes upon it in decades. It was an event we continue to refer to as our ‘Indiana Jones’ moment. The box contained two of Aloha’s hand-written diaries along with her original expedition passport, annotated maps, and dozens of candid family photos dating back to her birth. The contents were in a very real sense our ‘Rosetta Stone’. The maps of Africa with notes and routes drawn in red grease pencil showed us exactly where the expedition drove and what alternative directions might have been followed due to lack of real roads and forced detours. Her passport gave us dates and places – international border entry and exit visas – to cross reference against Aloha’s own writings and published reports. The wealth of photos are among the only extant pictures of life before Walter Wanderwell when Aloha was still Idris, and ‘adventure’ was defined as a short walk to the beach at the bottom of the Hall property on Vancouver Island. It’s discovery allowed us to confirm or challenge many of the assertions Aloha made throughout her peripatetic life.

However, one day, Aloha’s daughter, Valri, placed a dust-covered tin box in our hands; no one had set eyes upon it in decades. It was an event we continue to refer to as our ‘Indiana Jones’ moment. The box contained two of Aloha’s hand-written diaries along with her original expedition passport, annotated maps, and dozens of candid family photos dating back to her birth. The contents were in a very real sense our ‘Rosetta Stone’. The maps of Africa with notes and routes drawn in red grease pencil showed us exactly where the expedition drove and what alternative directions might have been followed due to lack of real roads and forced detours. Her passport gave us dates and places – international border entry and exit visas – to cross reference against Aloha’s own writings and published reports. The wealth of photos are among the only extant pictures of life before Walter Wanderwell when Aloha was still Idris, and ‘adventure’ was defined as a short walk to the beach at the bottom of the Hall property on Vancouver Island. It’s discovery allowed us to confirm or challenge many of the assertions Aloha made throughout her peripatetic life.

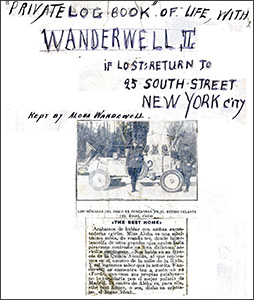

Walter forbade members of the expedition from keeping notes about their journey (diaries, specifically), and newspapers following their expedition and performances only reported what they saw or what they believed their audiences wanted to read. Aloha’s surreptitiously written first-person entries in these logbooks provide the rarest of glimpses into the day-to-day ‘mechanics’ of every aspect of the Wanderwell tour. We see what life on the road between two world wars was like through the experiences of a teenager who grows up before our very eyes. But are there embellishments? Does she gloss over certain events? Does she make anything up? Aloha, in later life, did edit some of the material, going so far as to literally cut and paste – physically removing one paragraph with scissors, while pasting in a newly written one with glue. What’s missing? And why?

Judicial sources and court records from the time regarding the events, trials, and tribulations of the Wanderwells – marriage, divorce, probate, tax, smuggling, and Mann Act allegations, arrest, incarceration, and trial are almost entirely non-existent. The microfilm reel we helped locate in the underground repository of the L.A. Superior Court records office on Hill Street (which then disintegrated upon being loaded into a viewer) hadn’t been unspooled since 1962. Its backup in a humidity-controlled vault in Chatsworth had never been looked at at all. We were told the original paper source material of William Guy’s trial from which those microfilms were made would likely have been incinerated 50 years after the event, which was standard operating municipal and state practice. A fifty-year destruction mandate meant the originals would have been destroyed in the early 1980s. The only reason we were allowed access to the evidence contained on that reel in the first place is we could prove that all people involved had long since passed away. The law states that privacy expires with the person.

Judicial sources and court records from the time regarding the events, trials, and tribulations of the Wanderwells – marriage, divorce, probate, tax, smuggling, and Mann Act allegations, arrest, incarceration, and trial are almost entirely non-existent. The microfilm reel we helped locate in the underground repository of the L.A. Superior Court records office on Hill Street (which then disintegrated upon being loaded into a viewer) hadn’t been unspooled since 1962. Its backup in a humidity-controlled vault in Chatsworth had never been looked at at all. We were told the original paper source material of William Guy’s trial from which those microfilms were made would likely have been incinerated 50 years after the event, which was standard operating municipal and state practice. A fifty-year destruction mandate meant the originals would have been destroyed in the early 1980s. The only reason we were allowed access to the evidence contained on that reel in the first place is we could prove that all people involved had long since passed away. The law states that privacy expires with the person.

Marriage and divorce records for Walter and Nell in Florida could not be attained, likewise, real estate, tax, and probate records regarding Walter’s estate and property holdings in Miami could not be found. If his land was sold off prior to World War II (it likely was) those records, if they still exist, are likely mouldering away in a box in the forgotten corner of some old warehouse. We were told as much by a Dade County court clerk. Historical records that far back are simply not a priority, and never were. For the most part, even old reference card files don’t exist, which means computerized backups that would have been based on those card files were never made.

In many cases, governmental cutbacks are to blame for the dearth of materials and the lack of access. Beginning twenty-five years ago government austerity programs hit the civil service hard; staff numbers at municipal and state levels were reduced and entire departments were folded into other portfolios. In many instances, we encountered overworked clerks who kindly passed our requests for records on to volunteers or interns who failed to locate the files.

In many cases, governmental cutbacks are to blame for the dearth of materials and the lack of access. Beginning twenty-five years ago government austerity programs hit the civil service hard; staff numbers at municipal and state levels were reduced and entire departments were folded into other portfolios. In many instances, we encountered overworked clerks who kindly passed our requests for records on to volunteers or interns who failed to locate the files.

These research obstacles will be familiar to any non-fiction writer. Attempts to confirm, challenge, or deny assertions made by the key characters of a biography becomes difficult if all you have is that person’s word for it. This is especially true of Aloha and Walter since they were engaged in peculiarly public endeavours and used ‘spin’ to explain, apologize, and promote.

It is possible that as this book gains wider attention new material, new ‘evidence’ will come to light, and we welcome that. Attics, basements, warehouses, and safety deposit boxes have a mysterious way of revealing themselves.

This is the story of Aloha Wanderwell’s amazing life, warts and all, based on the best available sources. It is the tale of an extraordinary woman who welcomed risk, adventure, and accomplishment into her life. The four corners of Aloha’s world had wheels, and the ends of the Earth were merely a challenge to her perseverance and indomitable spirit. No roads? No worries.

Maybe Peter Pan had it right:

“All the world is made of faith, and trust, and pixie dust.”

Aloha certainly thought so.

(From the book’s ‘A Note On Sources’.)